Are hungry judges and tardy doctors ruining people's lives?

Two similar studies shed some light on whether being tired, hungry, or rushed at work might lead to problems for others.

Hungry judges

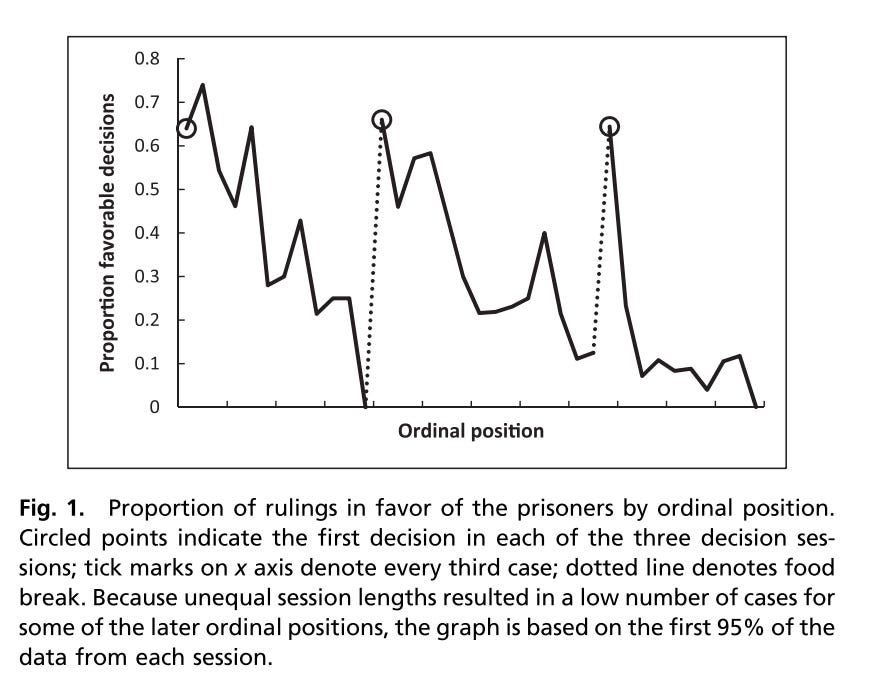

In 2011, a highly publicized research study by Shai Danziger, Jonathan Levav, and Liora Avnaim-Pesso examining rulings by Israeli judges found that over the course of the work day, judges tended to issue rulings most favorable to prisoners at the beginning of their work day and right after food breaks. Between breaks, the judges’ rulings became progressively less favorable until picking up again after the next food break, as depicted in the figure below:

The pattern persisted when the researchers compared rulings on cases with similar legal characteristics (e.g. severity of the crime, time already served, prisoner’s demographic characteristics), when they looked at each of the 8 judges individually, and after looking at overall time elapsed after a break (as opposed to the number of cases). So the data was very clear about one thing: the farther out from a food break, the less favorable the judges’ rulings.

The interpretation was that important legal rulings were being impacted by judges being hungry and/or in need of a break—factors that should have no bearing on such rulings. The study made headlines around the world, and it is often cited as an example of how arbitrary factors can get in the way of justice.

But was that interpretation correct? We’ll come back to this question, but first, let’s look at a similar study in medicine.

Tardy doctors

Like judges with a daily docket, doctors seeing outpatients also have a schedule of patients to see throughout the day, usually with a midday break for lunch (or, more realistically, scarfing down some food while attending some meeting or educational conference). For example, a doctor spending a whole day seeing outpatients might have two sessions, one from 8am-12pm and another from 1pm to 5pm.

As many of you have probably experienced, doctors seeing outpatients have schedules that are packed with patients, and it’s easy to start running behind. But if you’re the first patient of the day (or the first patient seen after lunch), you’re going to be less likely to have your doctor running late than if you’re one of the last patients in the session, where previous delays can add up. Doctors don’t like running behind either, so we might try to “catch up” by moving things along more quickly with later patients than we would have had they been the first patient of the day.

If a doctor is running behind, they might be more inclined to jump to a “quick fix” for a patient. For example, if a patient comes in asking for antibiotics for something a doctor is pretty sure is a viral infection, it’s faster and easier to just prescribe antibiotics than it is to have a conversation with the patient about why antibiotics aren’t the best choice at this juncture.

Alternatively, if a patient comes in complaining of pain, it might be easier to just prescribe an opioid than it is to craft a more elaborate plan that involves non-opioid pain medications, physical therapy, and other modalities. These “multi-modal” pain management plans can provide better pain relief than opioids, but it can take a lot of time and energy to put these plans together with a patient. Meanwhile, a potentially unnecessary-but-easy prescription can place a patient at risk for all of the complications associated with opioid use.

A study by Hannah Neprash and Michael Barnett (both collaborators of ours on other projects) looked at what happened to patients who were seeing their primary care doctor with pain complaints. The patients were all coming in with a new pain problem and had not been previously prescribed opioids in the past year. Using data from the electronic health record, they were able to see both when the patients were scheduled to be seen and when they were actually seen by the doctor.

They found that over the course of the day, patients who were seen later for pain complaints were more likely to be prescribed opioids than patients with pain seen earlier in the day—going from 4.0% of visits to 5.3% of visits. They also found that the more the doctor was running late, the more likely they were to prescribe an opioid (this was after accounting for the time of day of the scheduled appointment).

Meanwhile, they didn’t see any differences over the course of the day when it came to prescribing of non-opioid NSAID medications or physical therapy for patients with pain, nor were there trends in prescribing of non-pain related medications for high blood pressure or cholesterol. These conditions essentially served as control groups.

Neprash and Barnett estimated that if opioids were prescribed at the same rate over the whole day as they were during the first three appointments of the day, there would be 4,459 fewer opioid prescriptions among the 678,319 appointments they studied. Each opioid prescription carries risks of adverse outcomes—risks we wouldn’t want patients to have to bear if the only reason they were prescribed the drug was because of when they happened to be scheduled.

It appeared that doctors running late—maybe also tired at the end of the day—could have been putting patients at unnecessary risk from exposure to opioids. If this was the case, it’s evidence of the common complaint from physicians that we can’t practice the best medicine when our schedules are overstuffed with patients. But is this what was happening?

Assumptions

To establish cause and effect in these studies—i.e., to say that hungry judges and tardy doctors are causing problems—we have to rely on an important assumption: that the scheduling of these legal hearings and doctors appointments is as good as random.

Assumptions are impossible to prove (which is why they are assumptions), but we can find evidence to support them. If we’re assuming something is random, then it should divide people up evenly; we should see that judges’ cases and doctors’ patients seen at the beginning of a session are similar to those seen at the end of the session. For the judges, we saw similar crime severity, time served, and demographic characteristics at the beginning and end of sessions. For the doctors, patients were mostly similar, but patients seen earlier in the day were more slightly more likely to be men, to have chronic conditions, and to have longer appointments.

The reason we’re forced to assume is because there are many unmeasured characteristics of the cases for which it is impossible to confirm that they’re evenly distributed between those seen early in the session and those seen later. If there are details we can’t measure that both lead a case to go earlier or later in the day and lead to differences in verdicts or opioid prescriptions, then we can’t conclude that it’s only the scheduling that’s leading to the differences in outcomes. This phenomenon of “residual confounding” means that we can’t be sure that other factors besides timing are impacting the findings, in part or in whole.

While we can’t speak for what judges do, doctors’ offices do sometimes schedule patients they anticipate might put them behind schedule later in the day, to minimize disruptions to other patients. Judges offices might do the same thing—put cases they know will take longer (and that bend toward one end of the favorability scale) toward the end of the day. Identifying such cases in the data is really tricky, making it challenging to find evidence to support these assumptions.

So what’s the answer?

For both studies, we’re left with a big old “maybe.” Each study has some evidence supporting the assumptions. But the judges study only had a few characteristics that could be compared, and the doctors study showed some small differences on a handful of measured characteristics that, even when statistically accounted for, could be a signal of differences in unmeasured ones.

On the judges, a follow up simulation study has suggested that scheduling cases that will take longer and are more likely to be ruled favorably earlier in the day could explain the results of the original study by Danziger, Levav, and Avnaim-Pesso.

On the doctors, Neprash and Barnett note:

The results of this observational study should not be interpreted causally, although our findings were robust in several sensitivity analyses addressing selection bias. There could be unobserved reasons why patients more likely to receive opioids may have appointments later in the day, although we observed similar results in our analyses focusing on appointment lateness, which controls for hour of appointment.

We’ll also add that when looking at non-opioid prescriptions, like those for high blood pressure or cholesterol, you might think that patients seen later in the day would be more likely to be prescribed these medications if selection bias—more complex patients seen later in the day—were a big issue. Neprash and Barnett didn’t find any evidence of that, which is reassuring for their overall conclusions.

Ultimately, many of the studies we’ve visited in Random Acts of Medicine rely on similar assumptions in order to establish cause and effect. Disagreement on the validity of such assumptions is only normal—what is a reasonable assumption is often a matter of opinion. One rule of thumb we follow in our own work and in reading others’ is that while we can’t prove an assumption with certainty, the more evidence we can find supporting that assumption, the better.

as a patient or criminal in court would it be better to listen to the outcome on a full or empty stomach.

Really interesting study. I’d file this under- makes a lot of sense, but hypothesis generating, and maybe some thing to be aware if you’re a physician or patient.