England's tea craze: an unexpected boon for public health?

A new study using 200-year-old data shows how drinking tea helped keep the English out of hot water when it came to public health.

A hot cup of tea can really hit the spot if it’s a cold day, if you’re a bit congested from the umpteenth viral infection your children have brought home from school, or if your vocal cords need a boost (as we found out recording our audiobook, reading out loud for hours on end is a lot harder than it sounds!).

As Americans, it’s hard for us to truly comprehend the role tea plays in daily life in England (and the rest of the UK), where tea has been an extremely popular part of daily life for generations and remains so today. The history of tea in England is long and complex, but as a new study by University of Colorado economist Francisca Antman shows, it turns out that tea’s history in England has something to teach us about public health.

Tea in England

Once an imported luxury good enjoyed mostly by the wealthiest English families, tea had become an easily accessible good across social classes by the end of the 18th century. As Antman writes in The Review of Economics and Statistics:

Why then did tea emerge as the English national beverage? One important factor is the prominent role of the English East India Company (EIC), which had a long-running monopoly over trade with the Far East until 1834. Through its dominance in international markets, the EIC was able to bring so much tea into England that it was able to push other beverages, such as coffee, out of the market.

Another cultural feature that helped solidify England as a nation of tea drinkers was the advent of tea houses, where, unlike all-male coffee houses, women could purchase their own tea. This ensured that tea would become a more accessible drink, available to a wider population, and thus solidify its dominance as the country's national beverage. Tea gardens, which could be enjoyed by men, women, and families together, also enshrined tea as a cultural custom, as did the worker's tea break.

Notably, tea is made using boiling water. The act of boiling water helps make it safer to drink by killing disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and parasites, which at the time were a common cause of illness and death. Compared to other beverages that can be a source of cleaner water—like beer, wine, or coffee—tea was less expensive and had fewer side effects, so it could be drank all day long.

With the popularity of tea on the rise in England, it stood to reason that more people would be consuming safer water, because the water in their tea had been boiled. And if indeed they were drinking safer water, did that translate into reduced rates of death from water-borne illness?

Steeping in the data

From 1761 to 1834, the English increased their tea imports from China from about 1 pound to 3 pounds of tea per person per year. Over that same time period, death rates in England fell. Of course, tea consumption wasn’t the only change that occurred over that time period that might lead people to live longer—the Industrial Revolution led to many changes in daily life that could also have reasonably impacted mortality in England.

To tease apart any specific contribution of tea drinking to improved mortality, Antman needed to find a natural experiment. If there was an occasion where tea drinking increased suddenly relative to the other gradual changes during the Industrial Revolution, changes in mortality after that event that were out of proportion to what we would have expected from gradual progress could reasonably be attributed to the tea/boiled water.

The year 1784 produced one such event: this was the year import taxes on tea were significantly reduced, from 112% down to just 12.5%. Suddenly, tea was a lot cheaper to import and purchase. Below, we see the relatively sudden increase in tea imports after 1784. Mortality also improves after that year, and it appears to improve faster than it was improving before 1784—but from these data alone, it’s still hard to know if that was because of hot water use with tea, or something else.

Next, Antman figured out which areas of England would have had higher or lower quality water sources, based on geography (e.g. more running water nearby suggests higher quality drinking water), around the time tea’s popularity increased. If tea consumption led to people drinking safer water, then areas with lower quality water to begin with should benefit more from drinking hot tea than areas that already had cleaner water to begin with, right?

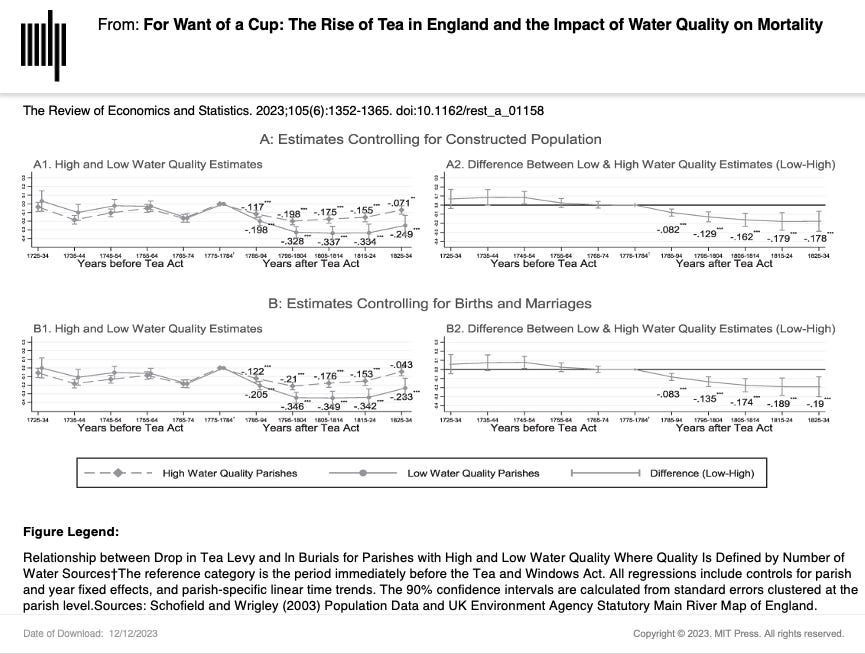

In analyses that accounted for changes in the population, she found that prior to the the 1784 drop in the tea tax, mortality rates (deaths per 1,000 people) were similar in areas with higher and lower water quality sources. After the tea tax was lowered, however, the improvements in mortality over the following 50 years were significantly different: in areas with high quality water sources, mortality rates dropped by about 7% over the next 50 years; meanwhile, in areas with low quality water sources, it dropped by about 25%.

Antman also looked at improvements in mortality in areas that imported different amounts of tea, finding that areas with low-quality water sources that imported more tea saw bigger improvements in mortality than when areas with high-quality water sources imported more tea.

So, was it actually the tea/hot water, or something else?

Could there have been something else that happened around 1784 that led to this reduction in mortality? The smallpox vaccine was disseminated around the turn of the 19th century, but Antman did several analyses suggesting that this didn’t explain the changes.

Could it be that areas with low-quality water sources simply benefitted more from the health changes brought on by the Industrial Revolution than people with high-quality water sources? In analyses that accounted for the relationship between changing income—where we might expect to see higher wages in areas thriving from industry—and mortality rates, Antman found no evidence to suggest that increasing incomes explained the observed differences between areas with high- versus low-quality water sources.

So while it’s possible that there was some other change that disproportionately improved health in areas with low-quality water sources, the evidence is all consistent with tea being responsible for improvements in health. Nowadays, of course, the quality of drinking water is no longer a major issue in England—but the traditional “cuppa” lives on.

Here in 2023 it's easy to forget how much of an impact readily available clean water had on public health. Unless you live in Flint MI or Jackson MS...

I've taken a liking to kombucha lately.