The unintended consequences of drug busts

Three simple yet convincing studies show some of the unintended consequences of opioid control policies

When policies are enacted to combat problems like the opioid crisis, it’s critical that we watch for unintended consequences of those policies that may create new problems. New problems can indicate oversights within the new policy, or they can show us a previously unrecognized aspect of the problem we were originally trying to solve.

Here, we highlight three studies that shed light on some of the potential unintended consequences of policies aimed at curbing the opioid crisis. This is by no means a comprehensive list; the first study is a recent one that caught our eye, and the latter two are studies we have worked on that shed some light on this topic. (If you know of any other interesting studies in this vein, please leave them in the comments below!)

Can police drug seizures lead to an increase in overdoses?

In a study published earlier this month in the American Journal of Public Health, a group of researchers from multiple universities took a look at data from Marion County, Indiana, the state’s largest county which contains the city of Indianapolis and about a million residents. They took a look at overdoses in the time and area immediately surrounding a police seizure of drugs, including opioids.

It’s natural to think that after opioids are seized by police, overdoses might go down in the immediate area, since there would be less opioids around (a direct “availability effect”) and because the seizure might deter illegal sales (a “deterrence effect”).

But that’s not how addiction works; people with opioid use disorder who are physiologically dependent on opioids are unlikely to simply stop taking opioids because their previous source went away. More likely, they’ll find a new source of opioids—and if that source isn’t supervised medical treatment, changing sources carries the risk of not knowing the potency of what they’re about to use. This, combined with the potential for reduced tolerance for opioids when patients go without them for a stretch of time, makes it easier to accidentally overdose.

The study found that in the 500 meter radius surrounding an opioid seizure, the rate of fatal overdose was twice as high compared to baseline in the 7 days following the drug seizure. While it’s possible that there may be other factors influencing the overdose rate in this time period, it seems likely that patients’ being unable to access their usual supply was indeed leading to the risks we just discussed. While the law enforcement arm of the response to the opioid crisis is clearly an important one, the study’s authors had some ideas for how safety after a seizure might be improved:

…Our study suggests that information on drug seizures may provide a touchpoint that is further upstream than other postoverdose events, providing greater potential to mitigate harms. For example, although the role of law enforcement in overdose remains a topic of debate, public safety partnerships could entail timely notice of interdiction events to agencies that provide overdose prevention services, outreach, and referral to care.

Do patients whose prescribed opioids are stopped also turn elsewhere?

For people who are prescribed opioids for a long period of time, discontinuing opioids is often most safely done via a slow taper. Stopping “cold turkey” leads to uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms that would be relieved by taking more opioids. People’s opioid prescriptions may be discontinued for any number of reasons, but if they’re stopped all of a sudden, it shouldn’t surprise us when people start looking for other sources.

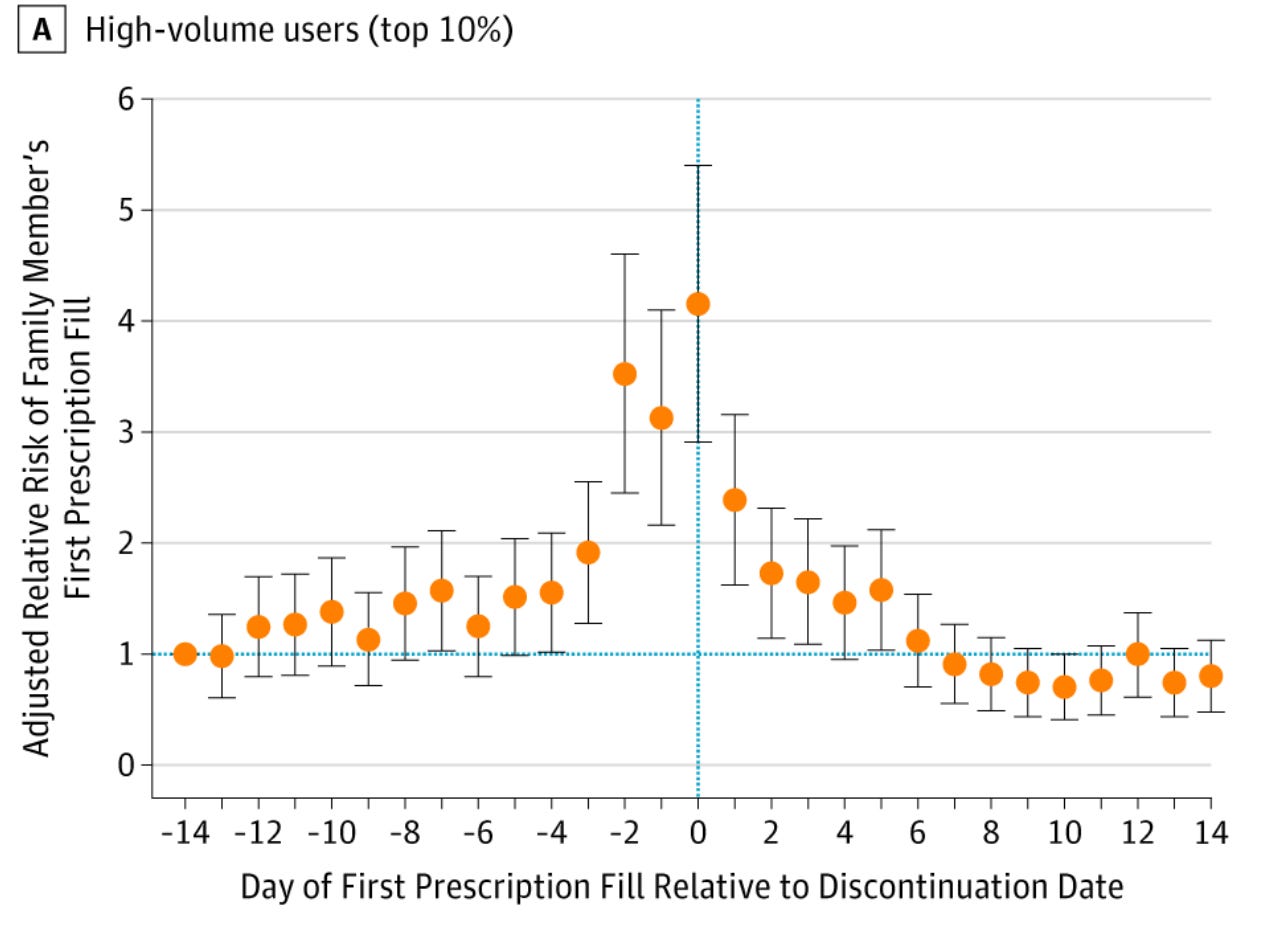

A 2019 JAMA Internal Medicine study by Bapu, Tanner Hicks, and Michael Barnett looked at people who were previously prescribed high volumes of opioids and whose prescriptions were stopped. They were interested in knowing what happened when those prescriptions were discontinued. Using an insurance claims database that linked patients and their family members, they found that when people who had previously been using large amounts of opioids had their prescriptions stopped, suddenly, their family members started filling first-time prescriptions for opioids at above-normal rates. It appeared that family members began seeking opioid prescriptions once the original patient’s prescription was stopped.

It’s unclear from the data what, exactly, was happening with opioids in the home, but what was clear was that once one doctor stopped supplying them, in a modest percentage of cases another family member started to fill the gap. Also concerning was that a new person was prescribed an opioid who might have otherwise not been involved with them at all, potentially placing them at higher risk of future problems with opioids.

The lesson? Suddenly discontinuing opioid prescribing in patients who are currently prescribed high amounts of opioids may not just be harmful for the patient, but it also may have unintended, dangerous ripple effects at home. Patients need gradual tapers and ongoing support from their doctor if they’re going to be stopping opioids.

Are (some) doctors circumventing opioid tracking programs?

Opioids remain commonly prescribed for patients who have just undergone surgery, which can obviously be a painful experience. Post-op patients, particularly those who go home right after surgery, often aren’t in any position to walk into a pharmacy to pick up their prescription opioids, so frequently a caregiver—often a spouse—is the one to pick up the prescription for them. But because of regulations surrounding the tracking of prescription opioids and how pharmacies might dispense those prescriptions, that may not always be so easy.

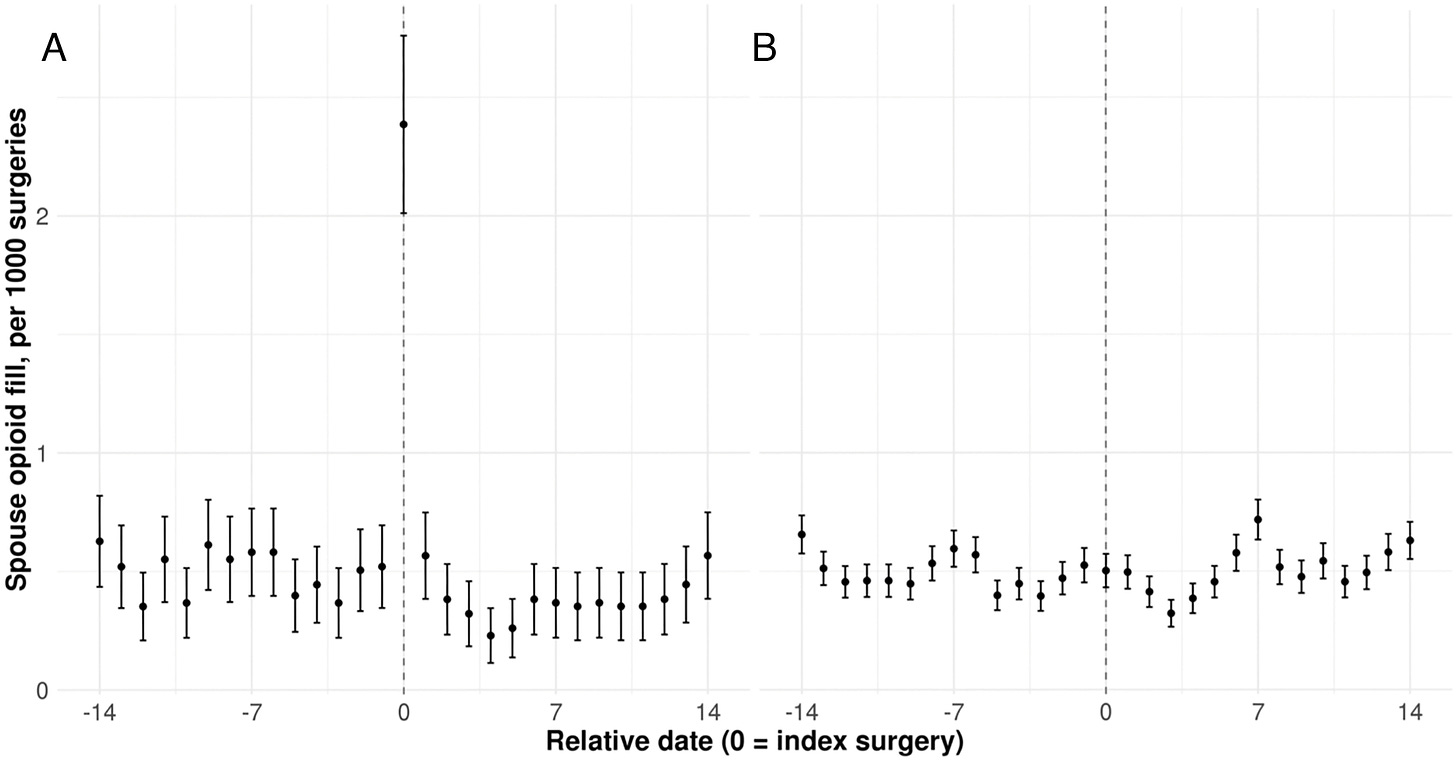

In a 2022 study in PNAS that we did with several colleagues led by Nathan Varady, we wanted to see if some surgeons were making it easier for spouses of their patients to pick up opioids by writing a prescription in the spouse’s name, rather than the post-op patient’s name. So we took a look at an insurance database to look at the chance that someone was prescribed an opioid on the date of their spouse’s surgery. While clearly a handful of spouses would be incidentally prescribed opioids on that day anyways, any increase above the baseline level on the day of surgery would be indicative of an opioid prescription to the spouse that was actually intended for the surgical patient. Here’s what we found:

When the patient undergoing surgery filled an opioid prescription in their own name, spouses were no more likely than usual to fill an opioid prescription on the day of their partner’s surgery. But when the surgical patient didn’t fill a prescription of their own, spouses filled opioid prescriptions with about 5.5 times higher odds than baseline on the day of surgery—suggestive that some surgeons were writing prescriptions to their patients’ spouses, not their actual patient, since there’s no other reason why the spousal prescription rate would be higher than usual that day.

Why is this a problem? Prescription drug monitoring programs track prescriptions of controlled substances, so that other prescribers can see what a person has already received and ensure safe and appropriate prescribing moving forward for any given patient. But if prescriptions are written in the wrong person’s name, these systems don’t work, and it becomes harder to monitor patients receiving these drugs.

We have to imagine that the surgeons writing these prescriptions are doing so with good intentions, and perhaps there are other policies—such as restrictions on who can pick up opioid prescriptions for whom—that are leading them to prescribe in this workaround way. Of course, these doctors shouldn’t be doing this, but it’s worth addressing why they feel the need to do it in the first place.

The opioid crisis been in the news for many years and despite being multifactorial in origin and extraordinarily complex, at its core, the problem is simple: opioids can relieve pain, yes, but they are also dangerous, addictive, and plentiful. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, no single solution that will get the job done, but there are many common-sense measures that have been taken over the past decade or two.

Their impact, collectively, seems to be a mixed bag. We’ve seen reductions in the number and size of opioid prescriptions from physicians, yet we’ve also seen ongoing alarming trends in opioid use disorder, overdoses, and access to opioids—prescription and non-prescription alike. Medicine and law enforcement alike must be on the lookout for unintended downstream consequences of well-intentioned policies.

Because this is a new newsletter, we would love your feedback on this post—what did you like, and what could be improved? Your comments will help bring the best content moving forward.

If you like what you’re seeing, please make sure you’re subscribed, then tell a friend and share us on social media!

I am a retired nurse of 39 years. I was still working when the rules started changing for opioid prescriptions. I know the healthcare professionals and organizations weren’t ready for this change. Even with doing their best and following the new guidelines, I can’t forget the patients who suffered because of it. I am aware of what led to these changes. I am aware of drug addicts versus people needing short term pain relief. I’m all for giving the doctors back a little decision making when it comes to treating their patients. I know this is starting an even bigger discussion of the growing involvement of insurance companies in the decision making of our healthcare. I still think we need to lean toward less government control and a more physician-based plan of care. Thank you☺️.

I’m an 80 year old man. I abused alcohol and amphetamine from age 13 to 40. I’ve been a recovery since. At age 65 I began using prescribed opioids for severe pain due to neck and knee injuries. At age 70 I was diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed amphetamine. At age 75 I had a partial knee replacement. Not wanting to increase the opioid dosage for the surgical pain I decided to slowly came off the opioids prior to knee surgery, and use a non-addictive drug instead. I believe that alcohol and opioids could have masked my ADHD for 57 years. So here I am needing a drug that can help me maintain a decent quality of health and life, and because of manufacturing restrictions of the generic form of amphetamine, I’m forced into a 600% greater monthly copay for the name brand. Of course the cost of all drugs continue to rise that don’t have a generic equivalent. Many mental health drugs have no generic equivalent, yet many believe mental health is this country’s most serious health issue. I apologize for the length of this post and if it’s a bit off subject.