Who will be tomorrow's doctors?

If past state rulings are any indication, a recent Supreme Court decision will lead to changes in who becomes a doctor.

Demographically speaking, the U.S. physician workforce doesn’t reflect the patients it serves. For example, Black Americans make up about 14% of the U.S. population but just 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic or Latino Americans make up about 19% of the U.S. population but only about 6% of physicians.

This is a problem for a number of reasons, some of which we explore in a chapter of Random Acts of Medicine titled “What Makes a Good Doctor?” Suffice it to say that diversity and minority representation in the physician workforce are good for both patients and the field of medicine, an idea with empirical backing.

Like other institutions of higher education, medical schools have tried to diversify their student bodies—and thus the future physician workforce—by considering students’ racial and ethnic background in the admissions process through affirmative action programs. In a 1978 ruling involving a medical school applicant, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that such programs could be used to help diversify student bodies in public higher education.

Later in the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, individual states banned the use of race-based affirmative action programs in public institutions, including state medical schools.

Last week, a supreme court ruling against UNC and Harvard (where we work) effectively put an end to race-conscious admissions processes across the country in both public and private schools.

The Past is Prologue

The best way to determine the effect that this most recent nationwide ruling may have on the physician workforce is to look at what happened when past, state-level affirmative action bans went into place at public universities.

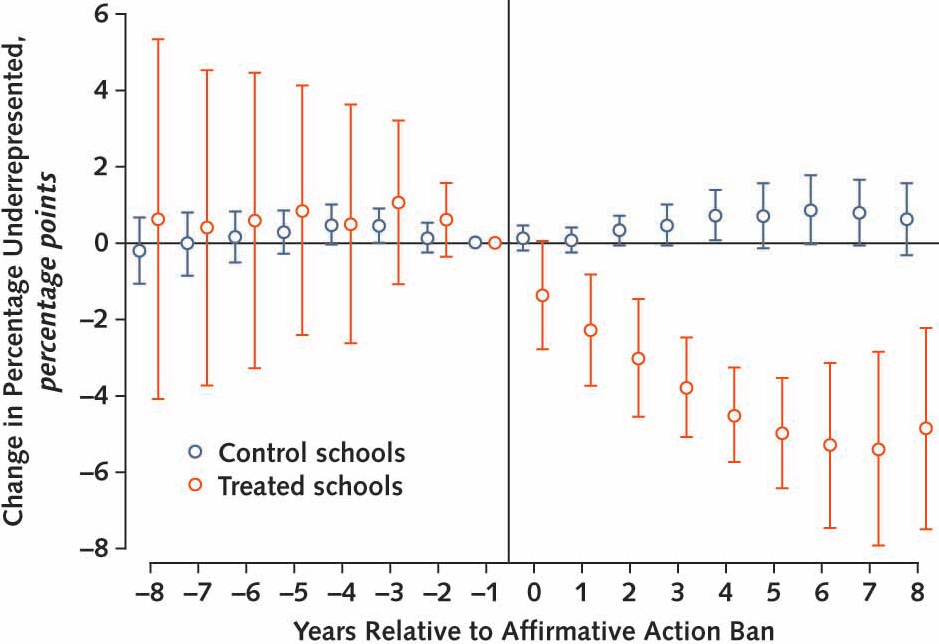

In a 2022 study, Bapu (along with Dan Ly, Utibe Essien, and Andrew Olenski) asked to what degree bans on race-based affirmative action programs impacted enrollment of underrepresented minority applicants in public medical schools. The natural experiment took advantage of the as-good-as-random timing of the bans with respect to when pre-meds would be applying to medical school. The study also examined what happened in other states where a ban never went into effect—states that serve as “controls” to the ones where bans were put in place.

Looking at the 21 public medical schools across the 8 states (TX, CA, WA, FL, MI, NE, AZ, OK) the study measured the percentage of underrepresented minority students (defined as Black, Hispanic, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander) enrolled in the schools in the years prior to and following a ban in the state.

In the public medical schools affected by a ban, the percentage of underrepresented minority students was stable in the years prior to bans being implemented, with these students representing approximately 14.8% of students the year before bans went into effect. But after the bans went into effect, that percentage steadily dropped over the subsequent five years—this was also the case looking at Black and Hispanic students specifically. The size of the effect was substantial, with an estimated absolute reduction of 5.5 percentage points due to the ban by the time the bans were in place for 5 years—suggesting the ban was responsible for reducing the schools’ underrepresented minority student enrollment by more than a third.

Meanwhile, in public medical schools in states without a ban that were similar to the schools in states with a ban, the percentage of enrolled underrepresented minority students was unchanged over the time period.

Moving Forward

Perhaps this finding shouldn’t come as much of a surprise—banning programs intended to increase enrollment of underrepresented minorities in medical school resulted in a decrease in enrollment. Why? Many refer to the “leaky pipeline,” wherein students who would have made excellent medical students disproportionately face barriers that prevent them from applying or matriculating.

A 2016 survey of minority college students interested in a career in medicine reported many barriers: lack of educational opportunities, difficulty finding information on how to get into medical school, difficulty connecting with physician mentors, difficulty paying for entrance exams and interviews, fear of not being accepted, lack of peer support, and high levels of family pressure to succeed.

If all of the almost 200 medical schools in the U.S. do what the schools in this study did in the several years following the state bans, we should expect a substantial decrease in underrepresented minority enrollment in medical school, which would cement reduced representation in the future physician workforce.

One medical school, UC Davis, has been focusing on the disadvantage applicants have faced in their academic careers prior to applying to medical school. Alternative approaches like this might help ensure representation in the physician workforce, so that tomorrow’s doctors—our future colleagues—are equipped to care for our diverse nation.

I disagree that all sectors of our world must be demographically proportional to the population in general. Further, using the argument that any racial group is best understood by someone of the same group is also a false conclusion.

Regardless, for doctors, the future is AI, which in 20 years will likely replace most, if not all MD's and AI's don't have any race or color.

It would be interesting to see if there is any relationship that could be established (rather than just inferred) between the results you report and the existing studies that show that patients of minority status, particularly black men and even moreso women, are statistically more likely to have their concerns dismissed/not taken seriously than white patients.