Let's brainstorm: Why are pedestrian fatalities on the rise?

A recent analysis by The New York Times highlights a disturbing trend that is without an obvious explanation.

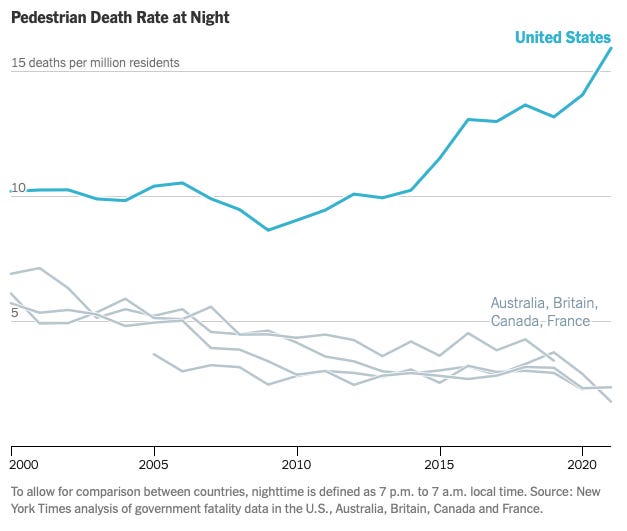

A reader sent us a recent article in the New York Times UpShot—an interesting section of the newspaper that dedicates itself to a mashup of data analysis and news—that showed a concerning trend: after nearly three decades in decline, the nationwide rate of pedestrian deaths in the U.S. has been steadily increasing since about 2009.

What is happening?

After breaking down the data from the U.S. Department of Transportation, authors Emily Badger, Ben Blatt, and Josh Katz noted two important points:

The rise in pedestrian fatalities was almost entirely driven by accidents occurring at night

When comparing similar data from other countries, there was no such rise observed in Canada, Britain, France, or Australia.

The data suggest that there is something placing pedestrians at higher risk that is unique to both nighttime and the United States. Some ideas come to mind right off the bat, which the authors at Upshot looked into:

Late hour, or darkness? The authors defined nighttime as 7pm to 7am, but in different parts of the country at different times of year, that time window doesn’t necessarily mean that it is dark out. To confirm that this was indeed related to darkness, they looked at what specific times of day were seeing the most pedestrian fatalities throughout the year. They found little spikes during morning commuting times during fall and winter, when days are shorter and morning commutes occur in the dark. But the biggest spikes were seen in the evening, with times varying by month based on the time the sun set; the spikes occurred latest in the summer and earliest in the winter, with sudden jumps occurring after daylight savings changes. In sum, the fatalities tracked precisely to darkness.

Who is getting hit? It’s easy to think that those at greatest risk might be vulnerable groups like children or the elderly. Children may not have the judgment or experience necessary to walk on roads safely at night, and they are smaller and harder to see by motorists. Elderly pedestrians may be at higher risk because they are more likely to suffer from hearing loss, vision loss, or cognitive impairments that make it more dangerous to be a pedestrian. Either way, one would expect those factors to roughly similar over time, which wouldn’t explain the reversing trend in nighttime pedestrian injuries starting around 2009. Regardless of that principle, it turns out that child pedestrian fatalities actually declined over that period, and there was only a small increase among those over 65. Those aged 18-64, however, saw the biggest increase in fatality rate. Why? We don’t know.

Where is this happening? The highest rates of pedestrian fatalities occurred in the Sun Belt states, but this has been a longstanding trend. The authors mention other research that suggests that pedestrian fatalities in downtown areas are on the decline, while those in suburban areas are on the rise.

Why is this happening?

The data alone don’t tell us exactly why this is happening, but there are a number of possible explanations that the authors put forward, none of which seems to be a slam dunk on its own, but taken together, might explain the trend:

Smartphones? The meteoric rise of the smartphone has taken place over this same time period, which can serve to distract drivers and pedestrians alike. Cars now have what seems to be an ever growing set of internal displays that could be distracting like a smart phone, despite the built-in safety mechanisms that disable some features while in motion. But our phones are distracting both during the day and at night, and smartphone use also has dramatically increased in the comparator countries. One difference between the U.S. and European countries is the less frequent use of manual transmissions—which force drivers to put down their phone to drive. But automatic transmissions are still popular in Canada, which hasn’t seen a rise in nighttime fatalities. (One testable implication of this theory would be to look at changes over time in driving accidents involving automatic versus manual transmission vehicles, under the idea that if growing cell phone use in cars is a cause of the overall observed increase in pedestrian injuries then one would expect sharper increases among automatic transmission vehicles compared with manual transmissions.)

More dangerous vehicles? Cars have gotten bigger, taller, and heavier over this time period, which makes it more likely that injuries to a pedestrian struck by the vehicle will be fatal. It also means that a driver may not be able to slow down as quickly when seeing a pedestrian in the roadway. The car experts interviewed, however, said that car sizes were getting bigger before 2009. What’s more, deaths from smaller vehicles like sedans have also increased. In sum, bigger cars probably isn’t the sole answer either.

More dangerous substance use? In the time since 2009, the U.S. has seen a changing drug landscape. While alcohol continues to play a significant role in pedestrian fatalities—the pedestrian is more often intoxicated than the driver—the use of other substances like opioids and cannabis has also risen over this time period with yet-unknown impacts on driver and pedestrian safety.

More pedestrians on dangerous roads? The authors posit that broader economic trends may be playing a role. “Nationwide,” they write, “the suburbanization of poverty in the 21st century has meant that more lower-income Americans who rely on shift work or public transit have moved to communities built around the deadliest kinds of roads: those with multiple lanes and higher speed limits but few crosswalks or sidewalks. The rise in pedestrian fatalities has been most pronounced on these arterials, which can combine highway speeds with the cross traffic of more local roads.” Additionally, homeless pedestrians may be living near dangerous roadways like freeways or in darkly lit areas, increasing their risk.

Now, as much as turning to the comment sections of major news articles would earn us an F if we were to submit this essay as a homework assignment, we thought there might be some good ideas in the over 2,500 reader comments:

Worse headlights? Echoing many other commenters, Ben from Boston wrote: “Newer cars have headlights that at their low levels really blind other drivers and make it very difficult to see darker objects at the periphery of the roadway. This is especially true of SUV headlights, as they are higher up.” The increasing popularity of brighter LED bulbs might impact the vision of drivers traveling the opposite direction, especially if the light beam is not aimed correctly (such as when installing an after-market bulb), making it harder to see a pedestrian in the road. While headlight technology has also advanced in the comparison countries, in Europe, adaptive driving beam headlights use cameras and sensors to provide maximal illumination while also preventing the beam from shining into the eyes of an oncoming driver. Adaptive driving beam technology was illegal in the U.S. until last year.

Worse clothing? A number of commenters noted there might be differences in what pedestrians tend to wear after dark that may be changing over time and be different between countries. If American pedestrians are more likely to dress in dark clothing or less likely to wear something reflective on a dark road, they might be harder for drivers to see. But it doesn’t seem like there was a significant shift in nighttime pedestrian fashion after 2009 that would explain this (if anything, brighter clothing resembling that of the 80s and 90s seems to be gaining in popularity).

Worse vehicle controls? A number of commenters pointed out that in addition to being a large, visual distraction, touchscreens within newer cars often contain controls to operate the vehicle. Older cars had dedicated buttons and dials that drivers could operate without taking their eyes off the road, such as for climate control or music. Some of these have vanished in favor of more complex touch screens that are less physically intuitive to operate, forcing even a focused driver to take their eyes off the road.

What do you think?

Many of the above explanations would be difficult to study, and there are presumably other contributing factors we haven’t discussed here. We agree with the Upshot authors that this concerning trend is likely due to a combination of factors, but what those factors are and to what extent each one is contributing isn’t clear.

We’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below. What do you think the primary contributors are? Are there big considerations missing here? Any ideas on how they could be studied?

I drive a stick shift, I cycle to work about 3 days a week, including night time commuting. I also live in Boston so...Ma$$holes abound...

Some of the things I would posit...

-our roads suck, lines are hard to see and the lighting is terrible

- absent or awful sidewalks

-

I think it's the large touch screens in cars but not because they are distracting (that would happen during the day as well) but because the brightness of the display narrows the pupils, ruining the driver's dark vision.