What Makes A Good AI Doctor?

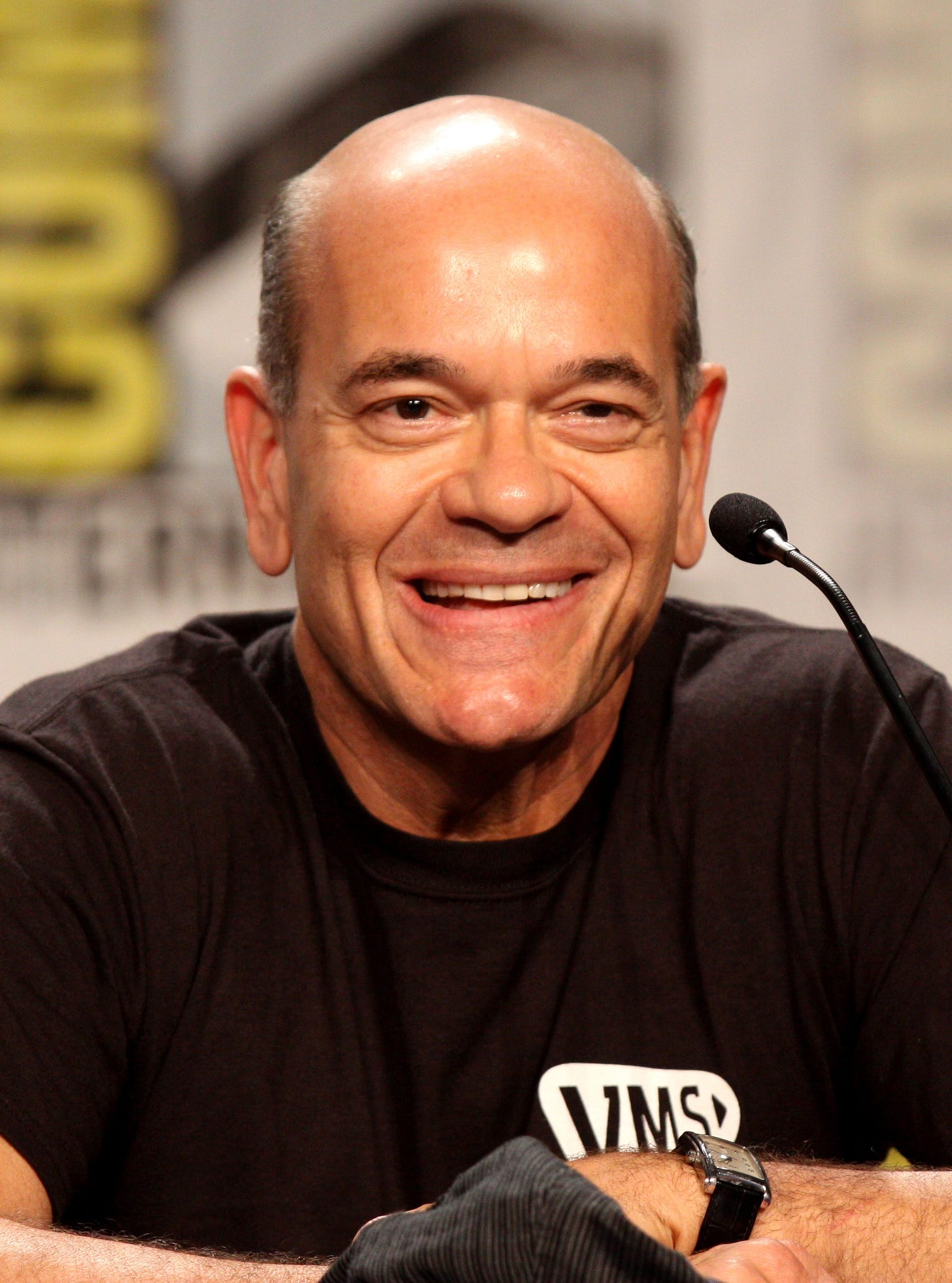

Chris chats with Robert Picardo, the actor behind TV's original AI doctor

Last week, we took a look at some of the real issues we’ll be facing with the increasing role of AI in medicine in the coming years. This week, we’re doing something a bit different to talk about AI in medicine a few hundred years in the future—at least as imagined through science fiction—in a conversation sparked by a chapter in the Random Acts of Medicine book (available here) titled “What Makes A Good Doctor?”

My TV doctor

For real doctors, it can be hard to watch fictionalized versions of our profession on TV. The contrived situations can be so inaccurate it’s distracting, or alternatively, they fail to offer enough of an escape from work to provide us relaxing post-dinner entertainment. But I imagine most doctors have some TV doctor that they were exposed to, likely before entering the field, that made a lasting impression.

For me, that TV doctor wasn’t one of the fan-favorites from E.R., which was very popular when I was a boy. It was the Emergency Medical Hologram from Star Trek: Voyager, an AI doctor, described here in a passage from Random Acts of Medicine:

Played by the actor Robert Picardo and referred to often as simply “The Doctor,” the Emergency Medical Hologram was a walking, talking, human-appearing, sentient computer program designed to serve as an emergency medical assistant in the event of a mass casualty event aboard the starship Voyager. But when Voyager is marooned on the other side of the galaxy without any living medical staff, he becomes the ship’s sole medical provider. He’s programmed with an extensive library of medical knowledge and technical skill—more than any “real” doctor could ever know. But as a computer program, he has terrible bedside manner and lacks the empathy and ability for human connection we expect of our medical professionals. Over the course of the show, the Doctor’s patients and shipmates end up teaching him some of what it means to be a doctor—and what it means to be human—as they journey across the galaxy.

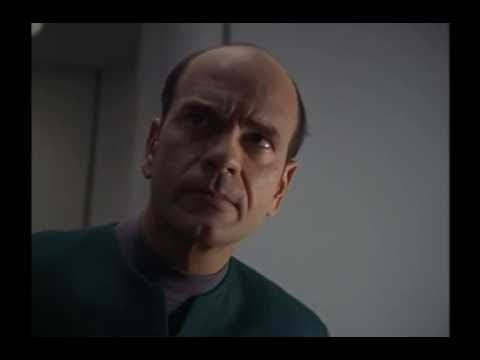

If you’d like to see him in action, here’s a clip of the Doctor’s initial “activation” from the first episode of Star Trek: Voyager:

I was about eight years old when Voyager first aired. As I grew up over the show’s 7-year run on TV, so did The Doctor. He started out as a smart and practical AI computer program, but eventually, he grew to be an empathetic, kind, and caring physician who embodied much of what anyone would want in their doctor.

As we discussed in last week’s post, AI is already a part of modern medicine. And while the technology is certainly far from being able to produce an AI doctor like Voyager’s that can provide comprehensive care, it’s not too early to be asking ourselves how we should be working on making a good one.

Robert Picardo, Hollywood’s AI doctor

Many of us have spent time thinking about the role of AI in medicine, particularly recently as we’ve seen apparent jumps in the technology’s capabilities like ChatGPT. While the technological capabilities of an AI doctor are one piece, the more challenging piece seems to center around how to get patients to want to receive care from one. For that, an AI doctor needs to be able to empathize with patients—or at least act like it—and navigate other complex human emotions to be able to engender the trust necessary in a good doctor-patient relationship.

I thought it would be beneficial to reach out to Robert Picardo, the actor who played Voyager’s Doctor, because he spent seven years thinking about this during the show’s run. Since then, like the rest of us, he has seen AI technology advance. While there is a large creative team behind any TV character, as an actor, Picardo was the one primarily responsible for making that character, well, human—or at least human enough to become a decent doctor.

Mr. Picardo carved out some time to chat while he was road tripping with his wife, a physician herself (the cardiothoracic radiologist Dr. Elizabeth Moore, whom Picardo describes as “my television doctor’s doctor”), to check out this year’s historic waterfalls in Yosemite National Park. After they sorted out some GPS directions, I started by asking him what he thought of all the talk of AI in the news. (Edited for brevity and clarity).

Robert Picardo: I have noticed of course that, especially in the last year, AI is in almost every news story or magazine article. We examined a lot of that in a science fiction context on Star Trek with my character—issues that are cropping up some 25 years out in a hypothetical way.

Chris Worsham: I think this idea of turning a computer into a human doctor is a question worth asking of people like actors, right? An actor’s job is to take something that’s not real—not human—and make it feel real and human.

RP: Let me tell you about my character. We started to shoot the TV pilot in 1994, during the health care debate of the first Clinton administration, and I always thought my character was kind of a satire of managed health care. So back then I thought of the character less that he was artificial intelligence than he was managed health care embodied—designed to do things very quickly, very efficiently, which of course doesn’t suggest good patient-doctor interactions.

A lot of the humor of the character was based on the fact that he was apparently willful—he didn’t always do what you wanted him to do—which in medicine, of course, could be a bit scary to have a computer program that is expressing its own will.

He had this incredible core programming of medical knowledge. I think in one of the early episodes, I say that I have the combined medical knowledge of 24 Starfleet medical officers and 4,000 medical textbooks—far beyond any amount that a single human brain could contain or learn in a lifetime.

He was supposed to have what were termed “emotional subroutines” so that he could develop and learn from interfacing with patients. However, he had absolutely no interpersonal skills whatsoever. In order to highlight that, I created a sense of artificiality to his character in the way I stood or the way I spoke. I had very little affect and barely ever smiled the first two years the character was on the air, because I wanted to have someplace to go as I developed a human personality.

We dealt with some core issues in AI as applied to medicine, or applied to any field, that are in the ether right now. If, as the Hippocratic oath goes, if an AI doctor is programmed to do no harm, what if that core programming could be overwritten? What if the AI could make decisions that were not in the best interests of its creators that it was supposed to serve? There was one episode where my character is trying to improve his personality profile by incorporating different famous people in history and mixing them together, and he inadvertently creates an evil alter ego.

CW: When I was younger, I thought that knowing all the science, and all the medical facts and techniques is what would make someone good at being a doctor. But your character, like me and every other doctor, has to make that transition from “I know the facts I need to know” to “I’m a compassionate human who knows how to care for people.” I could relate to the character in that way, making him somewhat of a role model, albeit one that is a computer. That, and your character, like me, had also lost most of his hair early in his medical career.

RP: I used to joke at conventions “If I am the embodiment of everything humanity knows about medicine in the 24th century, what ever happened to Rogaine?” You’d think they would have figured out male pattern baldness.

CW: Well they must have figured out that, hey, it doesn’t matter.

RP: That was the Patrick Stewart answer.

CW: I remember a lot of the episodes you just mentioned, centered on your character, where things go wrong with his AI in thought provoking ways. But also, if I think of the day-to-day interactions between the Doctor and shipmates, all of these little moments—they start to add up. Your character matures over the seasons. There’s this sense of humor, early on, which starts to make him feel very human.

RP: Oh, that was what made the role fun to play. The essential joke was that you could create a piece of technology to serve you, but that it would have a mind of its own. Early on he was cranky, he was arrogant and a little full of himself. I focused on the fact that he had all of this incredible power of knowledge in his program, but he had this Achilles heel that any idiot on the crew could turn him on and off like a light swtich. He had no control over his moment to moment existence; if he was turned off, he was no longer conscious, he was inert, and then when we has activated again, his consciousness resumed.

It was that dichotomy—the ultimate power of knowledge in my field, but the ultimate vulnerability as a member of this crew, when I ranked below everybody else as far as control over our individual selves. A lot of the early issues dealt with entitlements—if I am indeed the Chief Medical Officer, a full fledged member of the crew, why do I not get what everyone else is entitled to? It means you don’t just get to switch me off. When the Captain gives me the control to activate or deactivate myself, that was the first step in my journey to feel like I was being treated as an equal.

I used the word “feel,” but he literally was developing feelings—he wanted to be an equal, he wanted control over himself. And the next step was to devote some of his memory to hobbies, like opera, which is the most emotional form of human performance. I suggested to the Star Trek producers that my character start to listen to opera, because I thought it would be funny that a character who had no emotional affect whatsoever would listen to opera—I imagined my flaccid, blank face listening to an emotional aria. But they misunderstood me, and they wrote an episode where I’m singing opera—I was terrified at first but it ended up being OK. I thought it was a funny thing for a computer program to have hobbies.

CW: Do you think it made him a better doctor?

RP: Of course it did. As you said in your own situation, the first impulse was to know all the information, every fact about medicine. But that’s only part of the job, obviously. A patient has to feel you’re listening to them, not just processing a set of data. Taking in their questions, taking in their personal needs, and addressing other issues they bring up. Altering treatment can’t always be completely data driven, it has to be informed by what they say. It’s the human touch, if you will. The Doctor was programmed with the capacity to learn it, but you can’t program it.

He started to exhibit the human interactions that he witnessed, and he started to incorporate into his practice—he learned to smile, learned to have a twinkle in his eyes, learned irony. All of these things he learned to express helped him develop a personality that made him a much more successful physician. He could engender feelings like trust, or calm, or a sense of openness with the patient because of his developing access to empathy.

CW: I watched a clip of your appearance on Golden Girls, where you play another doctor with a terrible bedside manner. It was very funny.

RP: I have made a specialty, I suppose, in my career of playing characters that get off on the wrong foot with the audience—that the audience doesn’t like at first. They’re either self-involved or arrogant or full of themselves, but they also have some sort of a vulnerability that you try to show the audience so they will root for you to be less of an asshole.

Those are fun characters to play, versus the guy who is supposed to be immediately trustworthy and lovable. It would be boring to play the old school TV doctor Marcus Welby, played by Robert Young, just having that sweet, toothy angular smile like “you know you’re in good hands now.” You may want that as a patient when you go in, but it’s not a terribly interesting character.

CW: He was also not particularly realistic, either.

RP: The patient wants to feel like they’re in calm and steady hands, but often the patients come in with anxieties that are going to make your job challenging no matter how good you are with your bedside manner. All of those self-corrections that a doctor has to make in the moment—I have a very nervous patient, or I have bad news to deliver—there needs to be that human touch that mediates the information, no matter how automated medicine becomes.

CW: So you played a beloved AI doctor on TV for seven years. You’re married to a doctor. Presumably, you’ve been to doctors over the years. What do you think makes a good doctor?

RP: I guess a doctor who listens, first and foremost. I’ve seen doctors while the patient is talking—I can see in their eyes, they’re counting down the seconds before they get to begin. Most of the doctors I’ve had, I feel they listen well. I’ve had the same internal medicine doctor since I was 27 years old. We have this amazing history together. But he also seems to be up to date, he reads, and he keeps up with the developments.

My character on Star Trek was influenced by my pediatrician; I just loved him. He was a very kind, calm man. He was Italian, and because we were Italian, we went to an Italian doctor. I had a childhood ambition to be a doctor, a pediatrician specifically, because I could see that my mother had enormous trust in him and always felt good about bringing her children to him. I thought he was about as calm and empathetic a person as I have ever met. Part of what makes a great doctor, in addition to their knowledge and experience, is their empathy and they interact with patients to put them at the best possible ease and create trust.

CW: I don’t want to disrupt your vacation any more that I already have, but I did want you to know that growing up with your character has probably, in some subconscious way that I can’t pinpoint, impacted my own bedside manner for the better. So I want to thank you for that, and also thank you for your time today.

RP: Thank you, Chris. Thanks very much.

such a great idea for an interview!

If medical treatments and resultant success or failure outcomes couldn be fed into an AI algorithm maybe better health care results would happen. It would be a great physician assistant to physicians. imho